Moulins à vent

/This next recipe in La Pâtisserie des Rêves by Philippe Conticini brings home ever more clearly the importance of proper recipe testing and editing.

Remember, I'm using this book as a springboard for discussions regarding recipe interpretation, techniques and dos and don'ts. It is NOT my intention to follow the recipe to a T! Au contraire! I use what I've learned over the years to adjust the recipe and its steps in a manner that makes sense to me.

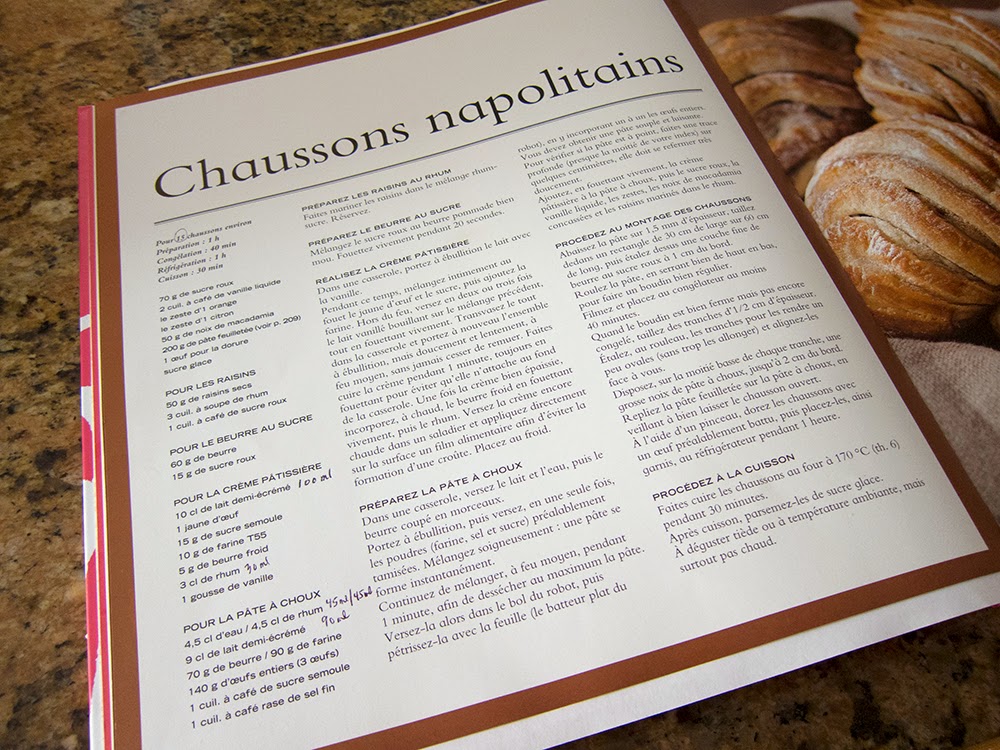

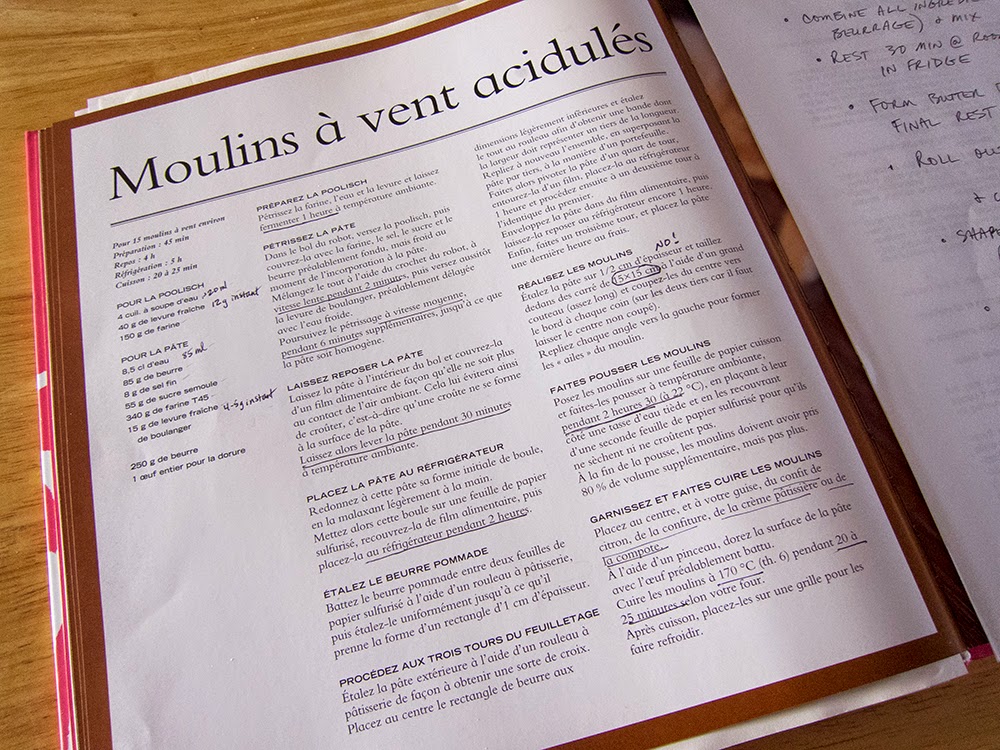

Here's the page from the book:

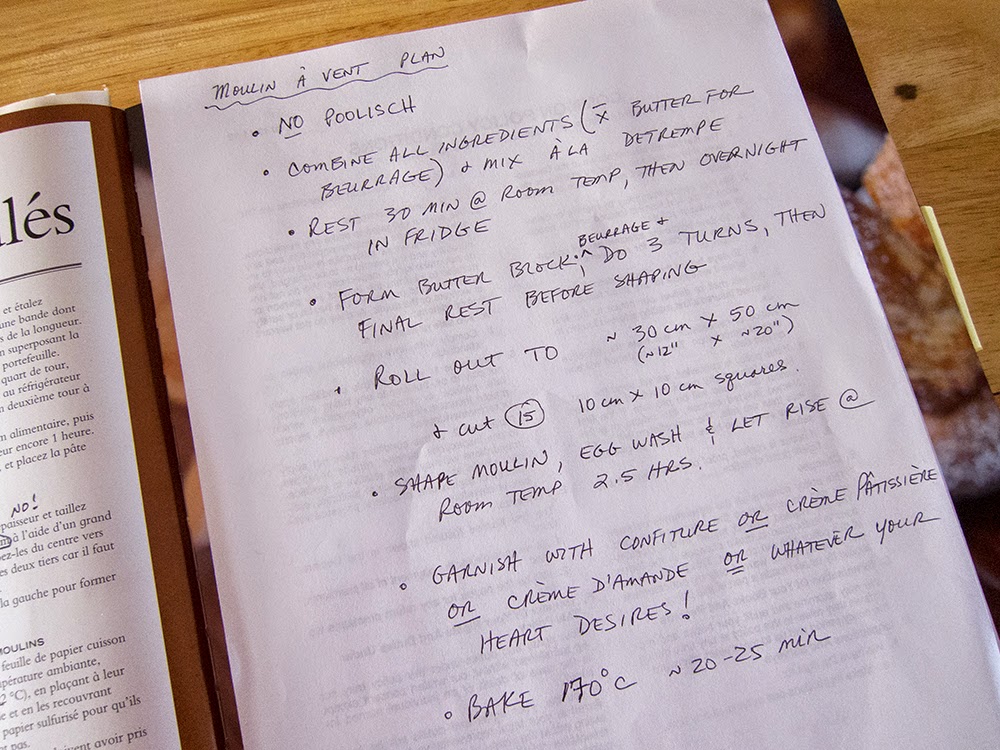

Here is the plan I developed based on my experience with similar doughs:

Rather than using a poolisch I made the dough as I would a détrempe for croissants, basically combining the ingredients for la poolisch and la pâte and reducing the total amount of yeast to 8 gm of instant. I also had to add more water than the recipe indicated in order to moisten the obviously dry dough mixture.

I gave it a good overnight rest in the refrigerator (where it develops some of its structure and flavor.)

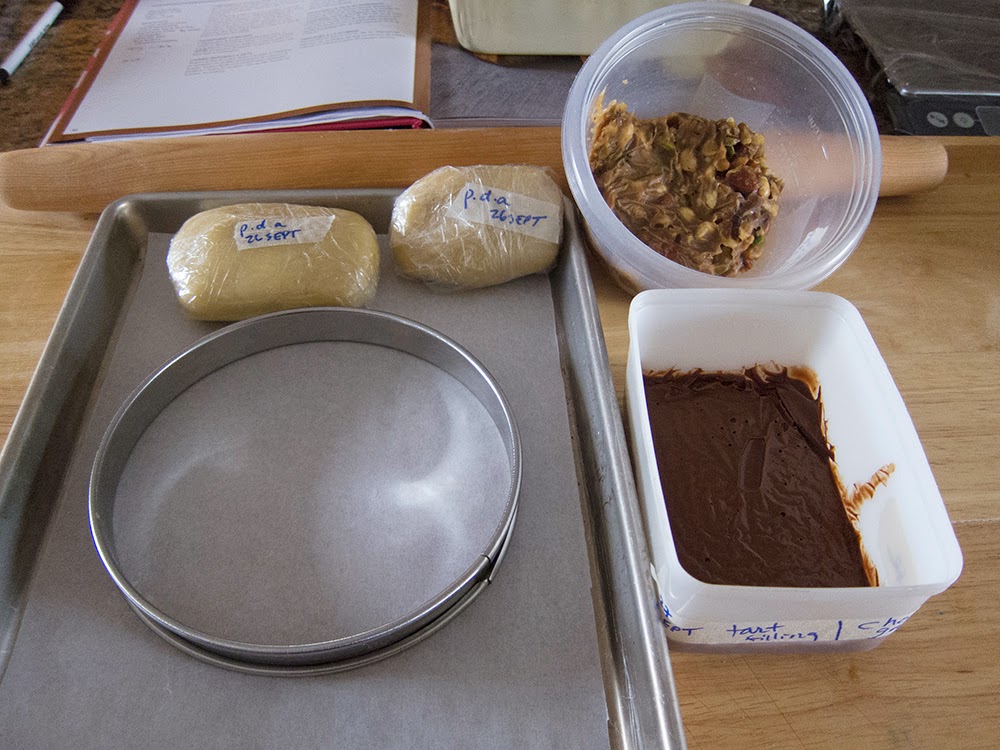

The butter block is ready:

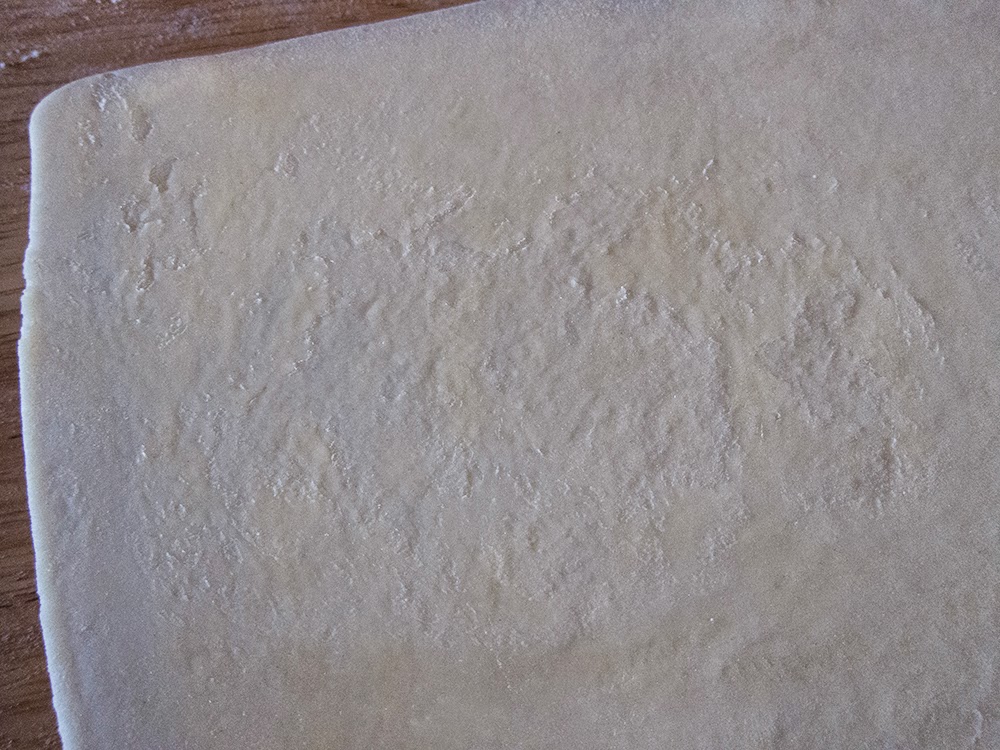

The dough is rolled out into a diamond and the butter placed in the center. I found this dough to be a bit stiff and dry, even with the additional water I added during mixing. Ultimately it did hold together OK, but see how the edges are somewhat cracked?.

The butter is enveloped by the dough:

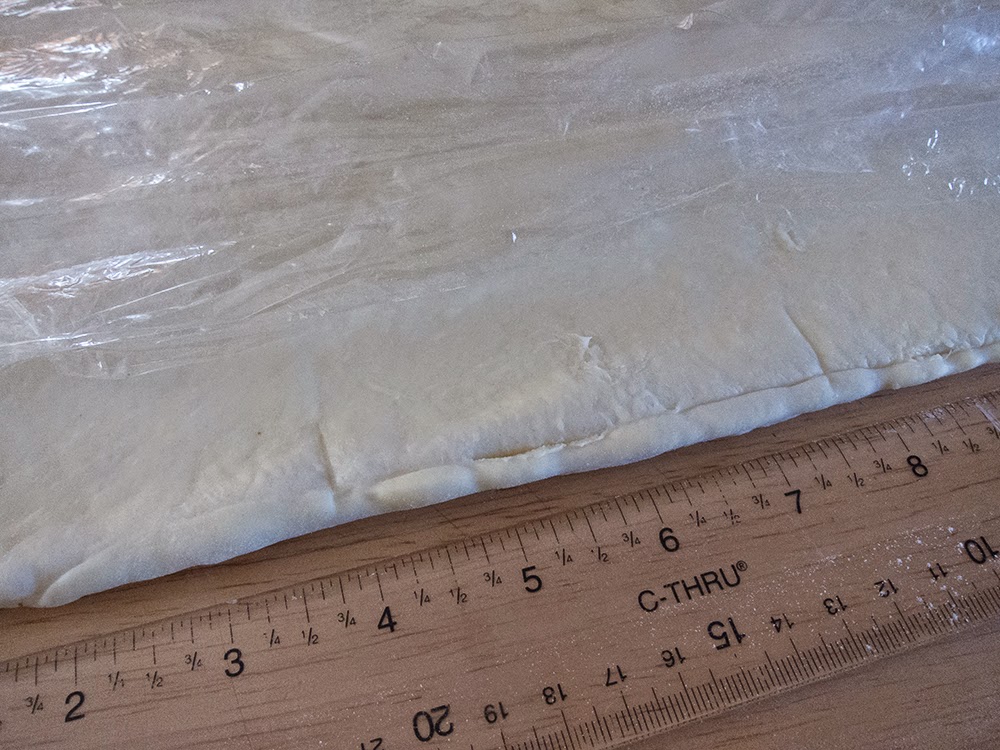

Then rolled out into a rectangle:

And the first three-fold and turn is done:

I found this dough to be similar to that in les croissants recipe - stiff, not easy to roll and the butter tending to break through.

This dough gets two more turns and a final rest in the fridge before rolling it out for cutting and shaping.

Now, here's a major flaw with this recipe. It states the yield is 15 moulins and instructs that each piece be cut into a 15x15cm square. In order to roll this quantity of dough out to create that many pieces of that size, you would have to roll it far larger and thinner than the 1/2 cm the recipe instructs. Plus 15x15 cm is HUGE for an individual pastry!

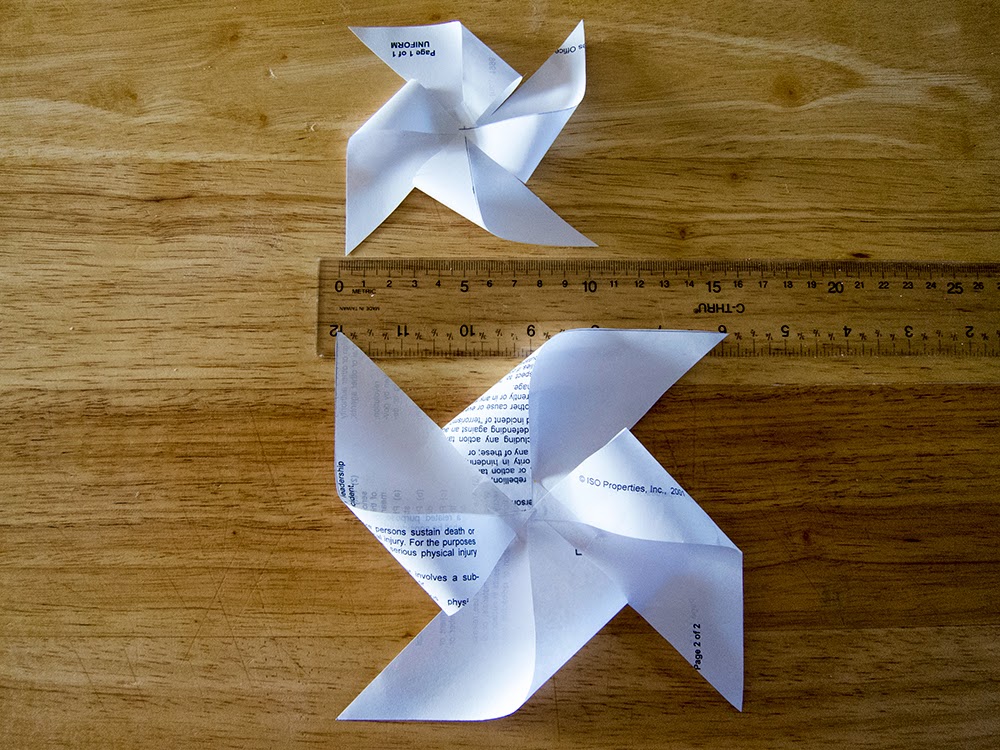

I opted for 10x10cm squares (just like when making Kouign-amann), a much more reasonable size for this quantity of dough, as well as for the finished pastries. Here are a couple of paper templates to show you the difference in sizes.

The dough is rolled out, cut into 10x10cm squares, slits cut to the corners, leaving the center intact.

Every other corner is folded into the center to create the lovely moulin pattern. It takes me back to my quilting days!

I used egg wash on the dough tips to stick them down. As you'll see, it wasn't that successful!

Now for a 2-2.5 hour rise at room temp. Notice how the tips have pulled away from the center, especially in the second picture - quite a mess!

Before I garnished these with a mixture of crème d'amande and apricot jam I had to gently push the tips back into the center - not an easy task with already risen dough.

Add a sprinkle of almonds et voila!

Next time I would roll my dough a bit thinner before cutting the squares since I ended up with 10 pieces instead of 15. I should have let it rest and relax a bit more before rolling it to my originally planned 30x50 cm rectangle. Patience, patience Susan!

The baking time of 20-25 minutes was pretty consistent with the recipe. Always watch how the browning is progressing and adjust your oven temp up if too pale and down if browning too fast.

And here they are!

I had hoped my windmill shape would have remained more distinct, but instead the tips kind of melded together during baking. Perhaps rolling the dough thinner would help that.

The flavor was good, although Steve and I thought they needed a little something, so we added a schmear of apricot jam to liven things up.

All in all this was another good learning experience. I am less and less enthralled with the book La Pâtisserie des Rêves due to the inconsistencies and poor editing I have encountered (leading me to believe that these recipes were authored by different people.)

For example, these moulins are made with laminated dough, the techniques for which should be consistent from recipe to recipe. Yet, the instruction for the beurrage (the enveloping of the butter in the dough) for this recipe is completely different than in les croissants, which uses the same technique. The author even forgets to tell you to fold the dough over the butter before you start rolling it out!

I'll put Philippe Conticini's book aside for awhile, although it continues to hold some allure with more enticing sections like goûters d'enfance, les classiques, et les tartes de saison, just to name a few!

In the meantime this coming week I'll be in Norwich, Vermont taking a 4 day artisan bread class at King Arthur Flour. What a great getaway and perfect blogging opportunity!